Organizing Resources

Check out our newest zines!

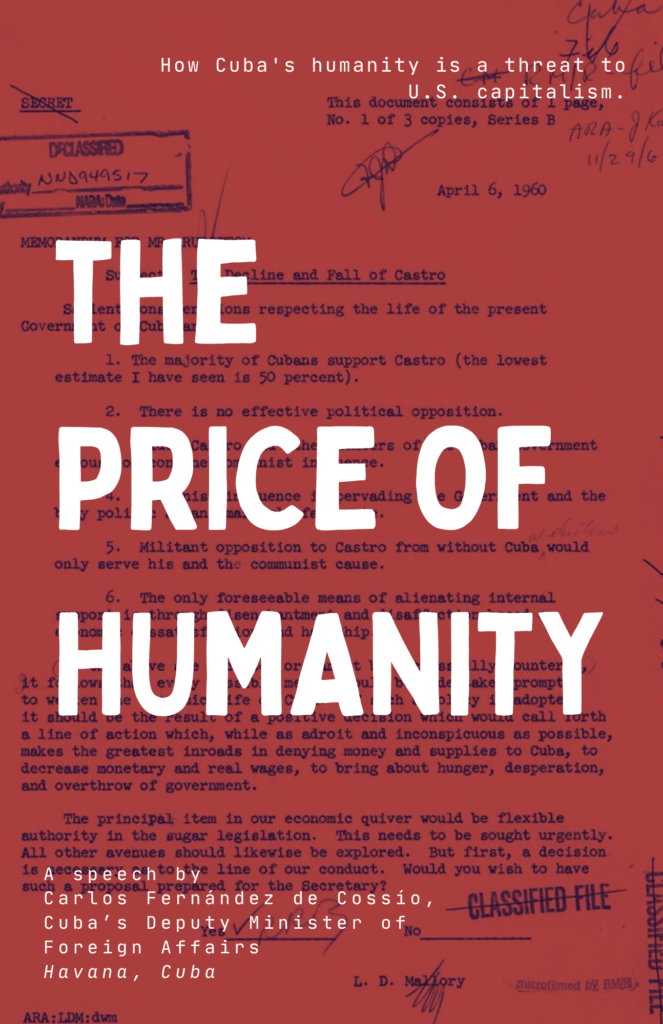

Read The Price of Humanity: A speech by Carlos Fernández de Cossío of the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Pastors for Peace Caravan on current relations, the blockade effects and the major importance of solidarity. This booklet gives great insight to the inner workings of the sanctions that the U.S. has implemented against Cuba for the last 60+ years, and how this severely limits the island’s ability to participate in global trade and access the most basic of resources like food, fuel, and medicines.

For over 60 years Cuba has been under a genocidal blockade by the U.S. This report reflects on how the policies of the U.S. on Cuba cause suffering across all major sectors of society. Despite this, Cuba is able to provide so much for the world due to its commitment to international solidarity.

Watch more Belly of the Beast

Frequently Asked Questions about Cuba

Like all nations, Cuba has a strong central government and security apparatus, developed in part to protect Cuban sovereignty from sabotage and other attacks sponsored by the U.S. government. Similar to our American Department of Homeland Security, Cuba protects its nation from rogue and hostile elements, both foreign and domestic. Dissent, public criticism of governmental policy, and policy input are allowed, and often encouraged, through proper, legal channels, often on the local level. Threats to the Cuban government and citizens are taken seriously and acted upon by Cuban legal authorities. While there are instances of human rights violations, the security apparatus includes a well-trained police force and a well-established legal court system where citizens accused of breaking the law are processed. Rehabilitation and re-education, as opposed to retribution and punishment, are the central organizing principles of the Cuban penal system. Their recidivism rate is reported to be 9%, compared with that in the US of 43%. Cuban prisons are administered through the Penal Directorate of the Ministry of Justice.

The U.S. embassy (previously the U.S. Interests Section) is located in Havana and is currently unstaffed. This means that Cuban citizens cannot apply for visas to travel to the United States without going to a third country. Despite both U.S. and Cuban investigations, there has been no resolution in regard to the “sonic attacks” alleged to have occurred in and around the U.S. embassy. This remains an unresolved issue between the U.S. and Cuba, although the overwhelming evidence indicates that Cuba had nothing to do with whatever these “sonic attacks” were, a conclusion the U.S. does not challenge. Before the COVID pandemic struck, millions of tourists from all over the world traveled to Cuba each year, finding it one of the most safe and welcoming nations to visit.

Cuba is currently facing its worst economic crisis since the 1990’s following the collapse of the support of the Soviet Union in what became known as the “special period”. The collapse of the tourist industry due to COVID, and the tightening of the US blockade under the Trump administration have created significant economic stress for the Cuban people. Waiting in long lines to buy scarce supplies is, unfortunately, a characteristic of Cuban life at the moment.

It is complicated to compare the Cuban economy with the US economy. Most workers in Cuba work for the state and receive low salaries, therefore have little disposable income compared to the US. However, the state provides economic subsidies, including food available at subsidized prices. Most Cubans own their own homes (so do not pay rent) and do not pay property or income taxes. Medical care and education are free.

The Cuban health system is world-known for its excellence. Their expected life-span is greater than that in the US. However, at the moment, in this time of COVID and the economic crisis, drugs and other supplies are in short supply.

The Constitution of the Republic of Cuba (whose current version in force was drafted in 2018, amended after a process of popular consultation, published, and then approved by the public in a national referendum on February 24, 2019) contains the following direct references to religion:

- Article 15 – The State recognizes, respects, and guarantees religious liberty.

The Republic of Cuba is secular. In the Republic of Cuba, the religious institutions and fraternal associations are separate from the State and they all have the same rights and duties.

Distinct beliefs and religions enjoy equal consideration.

- Article 42 – All people are equal before the law, receive the same protection and treatment from the authorities, and enjoy the same rights, liberties, and opportunities, without any discrimination for reasons of sex, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, ethnic origin, skin color, religious belief [emphasis added], disability, national or territorial origin, or any other personal condition or circumstance that implies a distinction injurious to human dignity. All people have the right to enjoy the same public spaces and service facilities. Likewise, they receive equal salary for equal work, with no discrimination whatsoever.

The violation of this principle is proscribed and is sanctioned by law.

- Article 57 – Any person has the right to profess or not profess their religious beliefs, to change them, and to practice the religion of their choice with the required respect to other beliefs and in accordance with the law.

Religion in Cuba is a matter of personal preference and, as in any society, its institutions and practices exist within a framework of law. It is recognized as a social force among others; it does not have privileges (e.g., tax exemption), nor may it be used as a means to undermine the norms of Cuba’s socialist system.

The history of Cuba’s, and the Cuban Revolution’s, interaction with religion is complex. The original indigenous peoples of the island practiced their own religious beliefs, which were forcibly and violently displaced by the largely Christian, largely Roman Catholic, European colonizers. Part of the colonizing task of integrating the indigenous under European rule was to acculturate native populations by converting them to what the colonizer defined as a “superior” faith, whose hierarchy and practices were more in tune with the colonizers’ culture.

As the colonial economy became increasingly dependent upon importing human labor, enslaved Africans brought their own religious beliefs and practices with them – traditions which often provided comfort and community to people surviving under the dehumanizing conditions of slavery. The religion of the Yoruba people was functionally very similar to Spanish Catholicism, with a focus on intervention of saints. This provided a cover for Africans to continue to practice rituals related to their traditional deities and holy figures, and these syncretistic popular religious practices continue to this day. Other “Cuban religions of African Origin” are widely practiced, particularly Palo Monte from the Congo and Abakuá, a men’s secret society.

The Roman Catholic hierarchy, however, remained almost entirely Spanish until the end of Spain’s colonial enterprise in Cuba. While Cuba was identified as a majority Catholic country, most institutional energy was spent on educating the elite in Catholic schools, and most clergy were foreigners, not necessarily identified with the culture of their local faithful.

As the United States rose to become the dominant economic power in the Western Hemisphere, North American Protestant denominations began to invest spiritual and material resources in their near neighbor, Cuba. Protestantism was considered culturally friendly to capitalist development and the modern office culture. Cuba was one of Latin America’s most heavily-evangelized countries by U.S. Protestant missionary efforts. Protestant schools began to attract the economic elite.

Throughout Cuba’s pre-Revolutionary history, churches were generally perceived as uninterested in, or unfriendly to, progressive social change. In rebellions against the 400-year-long Spanish rule, the largely Catholic expatriate clergy were seen to be allied with Spain. As Protestants became more visible in the 20th Century, members of these churches became closely identified with the churches in the US,. Following the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, and as the Revolutionary government increasingly identified itself as socialist, churches and practicing religious people were perceived – with some notable exceptions – as opposed to the massive social change that Cuban society was undergoing, and churches and religious institutions were sometimes used by the U.S. as vehicles for attempting to undermine revolutionary change. As Cubans whose economic interests were threatened by the Revolution began to desert the island and emigrate in large numbers to the United States, religious institutions were among the key vehicles for their resettlement, and, whether intentionally or not, became amplifiers of the exiles’ message of their persecution by the Revolution in Cuba. All these factors contributed to a mistrust of religion on the part of the Revolution’s early leadership.

Nonetheless, most Cuban religious believers, like most Cubans, did not flee the country but remained to become a part of the rapidly-changing society. The relationship between religious institutions and the Cuban government and Cuban Communist Party has continued to change. The earliest Constitution and governing documents of the Revolutionary period, while guaranteeing basic freedom of religion, excluded religious believers from Party membership and certain occupations. This changed, slowly but steadily. In 1991, the Party began to admit religious believers to its ranks and in 1992 declared it was not atheist, but a secular state, with separation of church and state.

Just two examples of critical roles played by religious leaders in recent years: the late Rev. Raúl Suarez, a Baptist pastor and ecumenical leader, in his role as an elected member of the Cuban National Assembly, was instrumental in halting the practice of the death penalty in Cuba. The late Rev. Odén Marichal, an Episcopal priest, seminary professor and also a National Assembly member, was the first coordinator of the Cuban Interreligious Platform, an interfaith forum focusing on international justice and peace. Presbyterian pastor Rev. Sergio Arce wrote extensively on the theological basis of “being a Christian in a Socialist Society”.

Churches and other religious entities find ways to be faithful both to their religious beliefs and their commitment as patriotic Cubans. Most mainline Christian denominations, as well as Jewish, Muslim and other faith communities in the U.S., now have relationships with counterparts in Cuba, and many actively advocate for an end to the U.S. policy of embargo and travel restrictions, which they find to be antithetical to their faith principles of mutual respect and humane treatment. As Cuba’s economy began to open to private enterprise, U.S. religious partners, among other activities and programs, responded to requests for aid in fostering micro-enterprises and sustainable agriculture projects.

As in other parts of Latin America, the US has used introduction of fundamentalist churches as a way to extend their influence. The Cuba Money Project has tracked US projects which seek to impose US values upon Cuba in ways that infringe on their sovereignty, including using planting of fundamentalist churches and theology.