Building a Domestic Agenda for Change

IFCO founded in 1967

In September 1967 a group of progressive faith leaders and activists founded the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization (IFCO) to direct funds from US churches to communities struggling for self-determination and justice. A young pastor, Rev. Lucius Walker, Jr., became the first Executive Director of IFCO. Ann Douglas later became Executive Director from 1974-1978 when Rev. Walker worked for the National Council of Churches. Under their leadership, IFCO would quickly emerge as the largest foundation in the US controlled by people of color by the mid-1970s.

The first national foundation directed and controlled by people of color, IFCO has acted as a bridge between predominantly mainline churches and community groups conceived of and run by people of color; as a broker for the channeling of interdenominational support; and as a resource bank supporting the work of congregations and organizations engaged in the work of community-building. IFCO has acted as a monitor, supporting self-determination by the poor, the hungry, and the exploited and ensuring that their needs are not sacrificed for the priorities of the privileged in American society. IFCO has acted as a catalyst and a conscience in the movement for social justice.

1969 National Black Economic Development Conference

IFCO organized and jointly led the the National Black Economic Development Conference, which took place in Detroit from April 25-27, 1969. The conference was organized by African American clergymen and business people in conjunction with interfaith social justice advocates to develop strategies for Black economic autonomy. James Forman, an author and American Civil Rights leader active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, and the International Black Workers Congress, presented at the conference the “Black Manifesto,” a call for reparations for African Americans–the first major call for reparations in the 20th century. The Manifesto demanded White churches and White synagogues pay $500 million in total to support Black companies and institutions, including a land bank and a publishing company for their complicity in racism. The FBI, already surveilling leftist and Black political activism under its COINTELPRO program, investigated and harassed IFCO staff and Foreman and threatened them with filing charges of extortion for calling for reparations. Neither IFCO nor Foreman cooperated with the FBI and Rev. Walker established a principled approach of non-cooperation with illegal and immoral US Government political persecution of progressive movements which would later become the bedrock of IFCO’s civil disobedience campaign against the US blockade of Cuba.

IFCO organized and jointly led the the National Black Economic Development Conference, which took place in Detroit from April 25-27, 1969. The conference was organized by African American clergymen and business people in conjunction with interfaith social justice advocates to develop strategies for Black economic autonomy. James Forman, an author and American Civil Rights leader active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, and the International Black Workers Congress, presented at the conference the “Black Manifesto,” a call for reparations for African Americans–the first major call for reparations in the 20th century. The Manifesto demanded White churches and White synagogues pay $500 million in total to support Black companies and institutions, including a land bank and a publishing company for their complicity in racism. The FBI, already surveilling leftist and Black political activism under its COINTELPRO program, investigated and harassed IFCO staff and Foreman and threatened them with filing charges of extortion for calling for reparations. Neither IFCO nor Foreman cooperated with the FBI and Rev. Walker established a principled approach of non-cooperation with illegal and immoral US Government political persecution of progressive movements which would later become the bedrock of IFCO’s civil disobedience campaign against the US blockade of Cuba.

Black United Funds

As part of IFCO’s work to build Black economic power, IFCO established and help build a network of Black United Funds that would direct monetary contributions to Black communities. According to a 1974 IFCO report:

As part of IFCO’s work to build Black economic power, IFCO established and help build a network of Black United Funds that would direct monetary contributions to Black communities. According to a 1974 IFCO report:

“Established charities do not fulfill the most important priorities of the Black community. Working people have been coerced for years into giving a percentage of their wages to the United Fund, United Way or some other philanthropy. But the people of the ghettoes and the barrios of this nation have not seen it returned.”

The Black United Funds were another way that IFCO sought to direct funds to communities struggling for justice and self-determination. As of 1974, Black United Funds were set up in eight cities, many with IFCO’s assistance, including Fort Worth, Houston, Dallas, Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago, Detroit and Norfolk, VA. The Norfolk BUF was headed by Rev. Milton Reid, an IFCO Board member for many years, who participated in numerous caravans to Nicaragua and Cuba. He was one of the Little Yellow School Bus fasters.

Walter Bremond of the Los Angeles Brotherhood Crusade, worked with IFCO to develop BUFs across the country. He eventually became President of the National Black United Fund, the umbrella organization for the BUFs.

Building Black Political Power

IFCO’s support of community organizations included those that sought to change politics on the local level. These included Committee for Unified Newark, organized by Amiri Baraka, which conducted voter education and registration drives and advocated for the election of one of the first Black mayors in the US, Kenneth Gibson in the wake of the 1967 Newark Rebellion. Elected in Newark, NJ in 1970, Gibson was the first Black mayor elected of a major Northeast city.

AIM and Solidarity with Indigenous Movements in the US

From its inception, IFCO developed a taskforce comprised of Native American activists to direct funds to Native community organizations, including the Coalition of American Indian Citizens, the Alcatraz Indian Territory Community, the Alaskan Federation of Native and the American Indian Movement (AIM). The Alaska Federation of Natives, among other activities, organized for reparations and land return of Eskimo and Intuit ancestral land in Alaska seized by the state government. In 1971, the Alaskan Native Claims Settlement Act was signed into a law, making it at the time, the largest land claims settlement (44 million acres) in US history and returning much of the seized land to Alaska Native Regional Corporations.

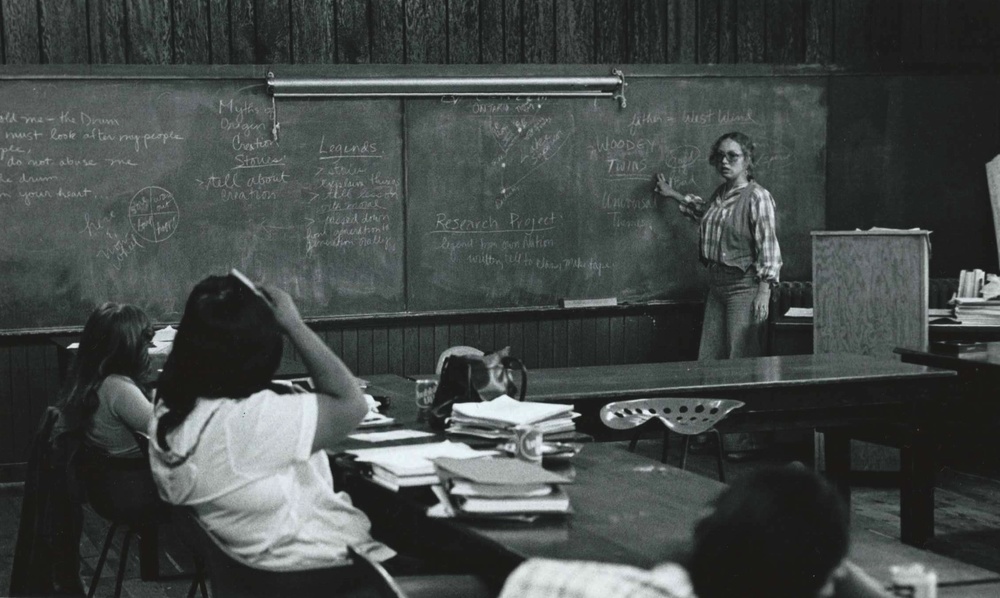

IFCO supported the American Indian Movement (AIM) for several years, including directing funds to the organization and providing technical support and solidarity. IFCO supported several AIM projects, including the Survival Schools which sought to educate Native children in their own cultures, histories and languages. IFCO also organized support for the Wounded Knee Trial activists and supported the 1972 AIM Trail of Broken Treaties cross country organizing tour which raised public awareness of Native issues and culminated in one of the largest gatherings ever of Native Americans activists and leaders in Washington, DC.

Education for Liberation

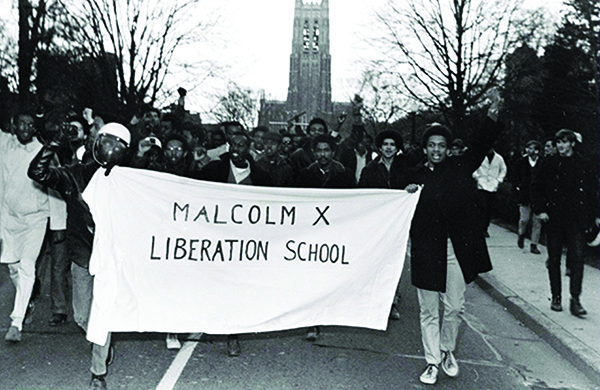

IFCO’s commitment to liberatory education began early on with its funding support of a variety of people of color community controlled schools, including the American Indian Movement Survival Schools, the Malcolm X Liberation School in North Carolina and the Universidad de Atzlán in California.

AIM challenged the racism against Native peoples in the social service and education systems by establishing the community-controlled schools to educate their children about Native culture and history with relevant curriculum. Established in 1970 in St. Paul, the AIM Survival School model spread across the country and AIM saw the need to create a Federation of Survival Schools to pool resources and expertise. According to an AIM brochure:

“A Survival School stresses Indian participation and control. Self-confidence and Indian pride are built in the students by a Survival School. These are qualities they need to have to survive in a white-dominated world. Too, the Indian culture–a way of life, a history, and a heritage–can survive only through our children. Survival Schools help fill the gap left by the deliberate destruction of our traditional communities and ways of passing this on to our children. To regain our rights and sovereignty, our children must study much that is not taught in public schools — such as treaties — as well as some things taught so poorly that our children come to believe they cannot learn. Cooperation, traditional in Indian life, is stressed in learning.” (Survival Schools brochure, IFCO Schomburg Collection)

IFCO Member Howard Fuller and other Black Power activists created Malcolm X Liberation University in North Carolina in 1969. While only lasting four years, the project was historic in that it was an experiment in higher education based on Black Power and Pan Africanist theory and principles and grew out of a Black student takeover of Duke University. Curriculum focused on Black history and technology fields, including agriculture, engineering, health and communications.

Farm Labor Organizing Committee

IFCO supported farm worker organizing by raising public awareness with the IFCONEWS newsletter and public events like Farm Workers Week, as well as directing funds to community organizations like the Farm Labor Organizing Committee. IFCO’s support lasted several years and many of the connections made during those years participated in IFCO caravans.

Largest People of Color Controlled Foundation in the US

By 1974, IFCO was listed as one of the 150 largest foundations and the largest people of color controlled foundation in the US, allocating $4 million — equivalent to $20.5 million in 2016 — to more than 150 community organizations. According to Rev. Lucius Walker, Jr., IFCO’s purpose was to support communities struggling for justice and self-determination:

“People of color in America must develop alternatives to the oppressive institutions now dominating their lives. Community organization practice has shifted from the streets to the process of analysis and planning for a new society. Even as analysis and planning are going on, new activity is picking up.

This new action for liberation is more than “getting a piece of the pie” or “carving out a comfortable niche in the system.” The pie is rotten and the system is evil. Independent alternative institutions are our promise for a new system and a new pie.” (IFCONEWS, May-June 1973)

Solidarity with African Liberation Struggles

IFCO established its Taskforce on African Affairs to connect Black movements in the US to African liberation struggles in Namibia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, South Africa, and Guinea Bissau, among other countries. IFCO developed a number of Africa solidarity projects, including RAINS, an early climate change activist campaign and organized a North American delegation to the 6th Pan African Congress in Dar es Salaam in 1974.

RAINS: Climate Change Solidarity in the Sahel

IFCO’s support of African Liberation struggles led to its creation of the RAINS project, which collected material aid relief for the drought-stricken Sahel region in Africa. IFCO’s relief effort was based on solidarity, not charity and clearly identified the cause of the extended drought to be climate change (see graphic from IFCONEWS newsletter) and the legacy of colonial and neo-colonial capitalism in the region. In stark contrast to the White Savior Complex based Africa programs that have become an industry, IFCO’s Africa relief programs sought to connect US Black communities with the Africa and involve multiracial constituencies to support relief efforts that would challenge neocolonialism rather than reinscribe it. School, college and community groups across the US participated in raising funds and material aid for the RAINS project.

FROM a 1974 IFCO Report:

“…experts estimated that six million more would die from famine and disease before the year was out. The International Red Cross disagreed, stating 13 million more were endangered.”

“The recent period of drought is not alone responsible for the vast desertification of the Sahelian zone. The earth has been robbed of its mineral wealth many years before by the French colonialists who used the area to farm cotton and plant peanuts for their use in trade. While French businessmen fattened off the exploited resources of the Sudano-Sahelian territories, its people lost the only economic resource they had. Land which had been used to graze cattle and sheep were ploughed under for the colonial crops. Thirsty vegetation drank up the water supply and no irrigation or artesian projects were built to replace it” (IFCO 1974 Report, 9).